March 29th 2016 marks the 500th anniversary of the founding of the Jewish Ghetto in Venice

On March 20th 1516 the Venetian Senate approved by a crushing majority of 130 to 44 for the enclosure of all Jews living in Venice in that part of town so called the New Ghetto.

A few days later, on March 29th the executive decree of the Senate was officialy announced: ‘The Jews must all live together in the Court of Houses which are in the Ghetto near the church of Saint Gerome. In order to prevent their wandering around at night two gates must be built on the side of the old Ghetto where there is a little bridge. The gates shall be opened in the morning at the sound of St. Mark’s main bell and shall be closed at midnight by four Christian guards appointed and paid by the Jews.’

The enclosure was further enforced by building two high walls, locking all exits, walling up doors and windows and by two patrol boats paid by the Jews to constantly navigate the canal around the area during the night. The Senate decided also to evacuate all houses in the new settlement from their previous occupants to give room to Jews who had to pay a higher rent than the landlords had previously been receiving

What were the events that brought to this conclusive and extreme decision?

Borrowing money on pledges at fixed rates of interest had been forbidden in Venice since 1254, anyone wishing to do so had to cross the lagoon and get to the nearby mainland city of Mestre.

In the 14th century Venice underwent a dramatic series of events, the black plague epidemic in 1348 and four wars against the archrival city Genoa which ended in 1381 causing a financial breakdown and a widespread money shortage. Consequently the goverment decided for the first time ever to let money lenders on pledges to enter the city. This legislation didn’t refer to the Jews, it just admitted anyone in the city for the sole purpose of letting quick and easy acces to credit to impoverished Venetians. All those who accepted the offer though were Jews but one.

In 1394 because the acute need for credit had passed the government decided the Jews should depart when the last charter expired in 1397. After that year no Jew could stay in the city for longer than 15 days at a time and had to wear a yellow sign on their clothing. Any future legislation required the Jews moneylenders not to settle permanently in the city but to stay for a just a limited number of days on yearly basis and leave until the next time frame. This regulation didn’t apply to Jewish merchants from elsewhere in the Adriatic who could come freely to Venice and send goods to the city helping Venice to compete in trade with other cities on the Adriatic seabord.

The 1503 charter signed with the Jewish moneylenders of Mestre permitted them to come to Venice in case of war for their own safety and to avoid the money they collected to fell in the hands of enemies safeguarding also the pledges of Christians that they held.

The 1503 charter signed with the Jewish moneylenders of Mestre permitted them to come to Venice in case of war for their own safety and to avoid the money they collected to fell in the hands of enemies safeguarding also the pledges of Christians that they held.

In 1509 an alliance of several European nations led by pope Julius II and including Spanish and Imperial troops overrun the Venetian mainland state getting a few miles away from Venice, it was the darkest moment in Venetian history. A great flow of refugees seek asylum in town among them several Jewish moneylender families who were given permission to reside in Venice and operate their banks. As the military situation improved for Venetians, the government realized that the presence of Jews in Venice will be beneficial in two ways. From one side Jewish moneylending banks will became a great source of taxation and from another they will provide easy access to credit for all urban poor Christians. By leaving their pledges in the Jewish banks they will get the money could help them survive in case of temporary difficulties like wars or a bad business year.

Therefore in 1513 a government office called the Council of Ten signed a contract with the Jewish banker Asher Meshullam from Mestre, he could engage in moneylending in Venice for 5 years in return for an annual payment. Two years later in return for a three-years loan, the Jews obtained the permission to sell second hands goods in nine stores. Jewish moneylending became then indispensable in Venice, not only helped to alleviate the economic problems of an increaseangly urbanized economy but it also avoided all Christians to violate the religion tradition who forbade any Christian to moneylend on interest to a ‘brother’ or a fellow Christian.

During a few years Venice became an exeption in Christian Europe. Jews could live wherever they liked in town although most picked a few parishes located nearby the Rialto market, the financial and trade center of Venice. A few very wealthy Jewish bankers also rented imposing palaces triggering strong feelings of envy among some Christians.

During a few years Venice became an exeption in Christian Europe. Jews could live wherever they liked in town although most picked a few parishes located nearby the Rialto market, the financial and trade center of Venice. A few very wealthy Jewish bankers also rented imposing palaces triggering strong feelings of envy among some Christians.

Despite the government’s policy of letting the Jews to reside in Venice, some fanatic Christian monks preached against them and demanded their expulsion. It was during Lent and Easter time when they repeatedly stirred the people to sak and plunder Jewish property. These preachers stressed that Jews were leaving among Christians in any part of the city but also that they wouldn’t stay indoors unseen during the Holy Week as they have been doing in any other city under Venetian rule. This state of things will finally turn the Venetian Senate to segregate all Jews as a compromise between their new freedom to reside all over the city and their previous state of official seclusion.

The first proposal of segregation was brought to the government’s attention in 1515 asking the Jews to reside in the Giudecca district, insulated by a large canal. On March 29 1516 the proposal of senator Zaccaria Dolfin, who said that the main reason for the Jews to stay in Venice was to protect the Christain goods in their possesion at the time of war, to enclose them within the city was voted and approved. The Venetian Ghetto finally came into being.

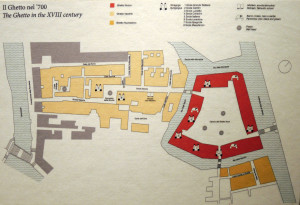

The area destined for the Jews to reside in town was a reclaimed island used originally as a dumping site for the waste produced by the municipal copper foundries. The process of casting metal was called in Venetian language ‘gettare’ and the area where the foundries were located was known as the ‘land of the getto’. Probably the final word ghetto was the result of how Ashkenazi Jews, who were among the very first settlers segregated in the new area, pronunced the original word getto.

This quarter will be the model for any future area of Jewish seclusion in Europe even before ghettos became mandatory in any Roman Catholic country in 1555 as a result of the bull issued by Pope Paul IV. These first Jews were of Italian and Askenazi provenance all in the moneylending on pawn business.

The rest of history of the Jews in Venice was mostly a Sephardic ‘affair’.

As there was no more room left in the first Ghetto a new one was open in 1548 for the next wave of Jews in Venice. They were Ottoman citizens and foreign guests deserving respect and protection although as Jews they have to live in the secluded area. This second group were mainly Iberians who left Spain and Portugal after the decree of expulsion of 1492 and 1496. Not to give up their faith they choose to leave and resettle in the territories then ruled by the Ottomans throughout the Eastern Mediterranean, the Balkans and North Africa territories. To them Venice was a city that already had an important Jewish settlement and a place where do business despite its waning role on trade and commerce towards the East.

As there was no more room left in the first Ghetto a new one was open in 1548 for the next wave of Jews in Venice. They were Ottoman citizens and foreign guests deserving respect and protection although as Jews they have to live in the secluded area. This second group were mainly Iberians who left Spain and Portugal after the decree of expulsion of 1492 and 1496. Not to give up their faith they choose to leave and resettle in the territories then ruled by the Ottomans throughout the Eastern Mediterranean, the Balkans and North Africa territories. To them Venice was a city that already had an important Jewish settlement and a place where do business despite its waning role on trade and commerce towards the East.

The final group of Jews signed a charter with the Venetian Senate in 1581. After the two previous ones, this one was composed again by Sephardic Jews arrived in Venice as ‘Christians’. After living in Spain and Portugal during many years as forcibly converted Christians, once in Venice were given the chance to revert to their original religion in peace without being investigated on their previous lifes. The reason for this bona fide agreement relied on the pivot role they played in Venice to keep the city still connected with the main Eastern trade routes when its heydays were already gone.

They were called ‘Marranos’ and they had left the Iberian Peninsula at the time of the Portuguese expulsion of 1496 and by larger numbers when the Inquisition was introduced in Portugal in 1539. And also beacuse they were suspected in Spain of still being Jews despite their ‘conversion’ . During the next years a growing number of so called ‘New Christians’ were able to flee the Iberian Peninsula and resettle elsewhere not just in the Eastern Mediterranean but also in Italy most notably in Ferrara, Leghorn and Ancona.

The third and last Ghetto was open in 1633 after the terrible plague of 1631 to give room to a last group of Sephardic Jews called in to bring new life in Venetian trade.

The gates of the Ghetto will be set on fire in 1797 when the French troops entered Venice putting an end to 281 years of segregation.

Further reading

Riccardo Calimani – The Ghetto of Venice – 1987 – M. Evans & co. This became the ‘standard’ history of the Venetian Ghetto and the Jews in Venice

R. Davis, B. Ravid plus others – The Jews of early modern Venice – 2001 – J. Hopkins University Press. A scholarly review on all aspects of the life of Venetian Jews